The man himself is categorically retro. On stage, Cameron Lew— head of the musical project Ginger Root— appears surrounded by CRT screens blaring bygone imagery; in music videos, his plotlines unfold in 4:3. For four years now, the band’s music has been inexorably tied to the aesthetic of an era 40 years back and an ocean away— they’ve carved a prominent place in the recent resurgence of all things Citypop. Though maybe not as unique as “Aggressive Elevator Soul”— what Lew used to coin his genre— “Modern Citypop” is an apt term to describe the past three Ginger Root albums.

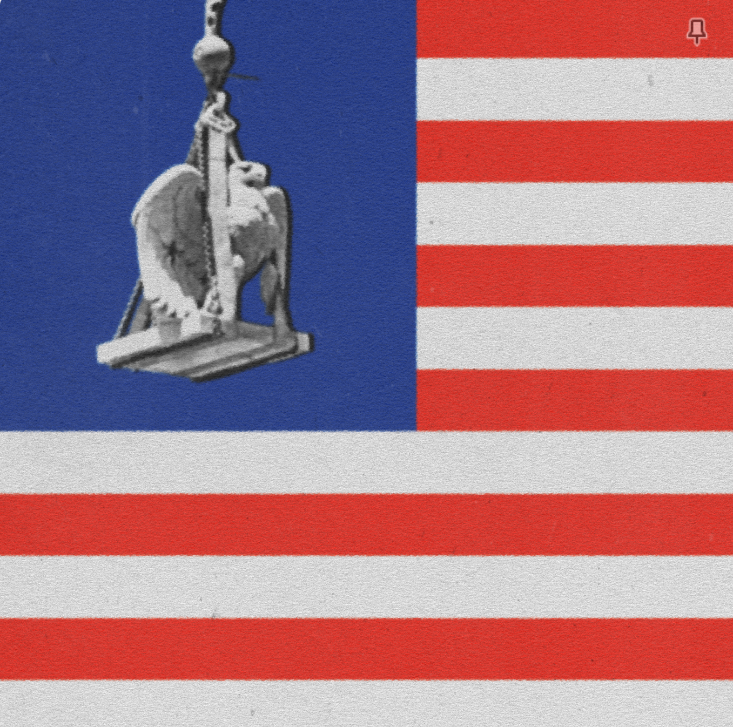

The original genre started in 1980s Japan, during a period of immense economic growth— this was the age where every TV, telephone, radio, VHS player, and camera in America was designed within a 50-mile radius of Tokyo. Within only two decades, the country had become the second most prosperous in the world. The culture of the time reflected such optimistic growth— in our case, a new music genre sprung from the likes of the previously well-respected Jazz Fusion wave, taking further influence from New Wave and (very notably) Yacht-Rock, which were making their way across the Pacific. What came out of this mashup was a genre aptly fitting the neon-coated atmosphere of the era— Citypop.

Though the band had released adjacent music in the past, Ginger Root’s relationship with Citypop starts with City Slicker. Released right as the genre was making a resurgence during the pandemic, every aspect of the album leans into its older influences: music videos had been transformed into entirely fictional snippets of movies and televised performances, and the sound of the band had gone from fairly standard indie-pop to an encapsulation of an era. Loretta, by far the band’s most popular song, sits midway through this album too: a prominent bassline underscores an incredibly catchy electric guitar riff and, among many musical flourishes, a saxophone solo— here, the resemblance to the genre is so uncanny the only true difference is that it’s sung in English (even then, Lew released a version in Japanese as a separate EP). On top of that, the music video for the song is a fictional televised performance, filmed on, of course, original period-accurate equipment.

Following City Slicker, Ginger Root’s relationship with Citypop peaked with the release of Nisemono, the band’s second most recent album. Released alongside a complete set of music videos set in 1983 that follow Lew’s fictional journey from ghostwriter to faux-idol, the album oozes postwar energy— the album art directly references the design of vinyl covers of the time, while the music videos advertise disposable cameras and nonexistent TV shows. Most notably, a full collection of the album’s music videos as well as behind-the-scenes footage and commentary from Lew was released with the album on, of all things, VHS only— a medium that hasn’t been used regularly for thirty years. Nisemono is, arguably, Lew’s most musically complex album— song structure varies, arrangements and production stand out as strikingly sophisticated— but it delves only further into the Citypop influence than ever. Yet there is something else there, something more self-conscious— curiously, the word “nisemono” translates roughly to “fraud.”

SHINBANGUMI was released about a month ago now. Where does it fit in? Ginger Root’s relationship with Citypop is, at this point, deeply embedded in the band’s sound and image. What their newest album does, as Lew has stated in interviews, is give this era of the band’s music a fitting send-off. The album’s story quite literally starts with Lew getting fired for refusing to make a sequel to, of all things, Loretta— before the first song of the album kicks in, he argues with a TV station executive for a seemingly genuine moment. He’s proud of what they made, but he can’t make another Loretta. He’s fired immediately after.

There is an undeniable groove. With songs like All Night— a thumping, bass and synth-heavy myriad of sound Lew described as “my attempt at club music”— and Take Me Back (Owakare no Jikan)— a seemingly direct homage to the 1984 song Stay With Me (Mayonaka no Door)— being stellar examples, nearly every song hits strong and stays with you, coming together as a genuinely phenomenal whole. That’s not all you’d notice on a listen, however— the entire album is laced with an ethereal feeling. Gone are many of the Citypop-esque starts and finishes, replaced instead with fades to static, sudden cuts, and blaring tones— going through in chronological order, you’ll suddenly find yourself in a seemingly genuine TV station advertisement or a bizarre piece of minute-long pure atmospheric melody. Music videos have been given a similar treatment, too: many, like the one for Only You— a surrealist showcase of what’s going on inside Lew’s mind as he’s rattled by the decision to work for a major network— delve fully into abstraction, while others, like There Was A Time, seem to be entirely set within the world SHINBANGUMI occupies. This abstraction, taken to a level far higher than any of the band’s previous works, serves a new purpose— the very fabric of the album feels like it is, in some sense, coming undone. Changing. SHINBANGUMI is finality, but it’s not the end— not by a long shot.

The glossy past of 1980s Japan is long gone now. General decline led to a slowing down of the so-called “Japanese economic miracle”, and nowadays those TVs, cell phones, speakers, and cameras are designed around the world. Since the end of that period, we’ve seen a time of generational nostalgia towards this era of culture, and nowadays it’s stronger than ever— Plastic Love, a song from 1984, hit Japan’s Top 10 last year. With what Ginger Root wants to do with their music, however, it seems like their foray into the resurgence of Citypop is coming to a close. Lew, and the band as a whole, want to do something new— maybe not a departure from their sound, but a distancing from this aesthetic. Nostalgia is beautiful, but it’s time to move on. Even though the story of the music videos themselves, through Lew’s story itself, the band’s message is clear— it isn’t over. It’s just the end of an era.