This is going to be out there, I know. You’ll have to hear me out.

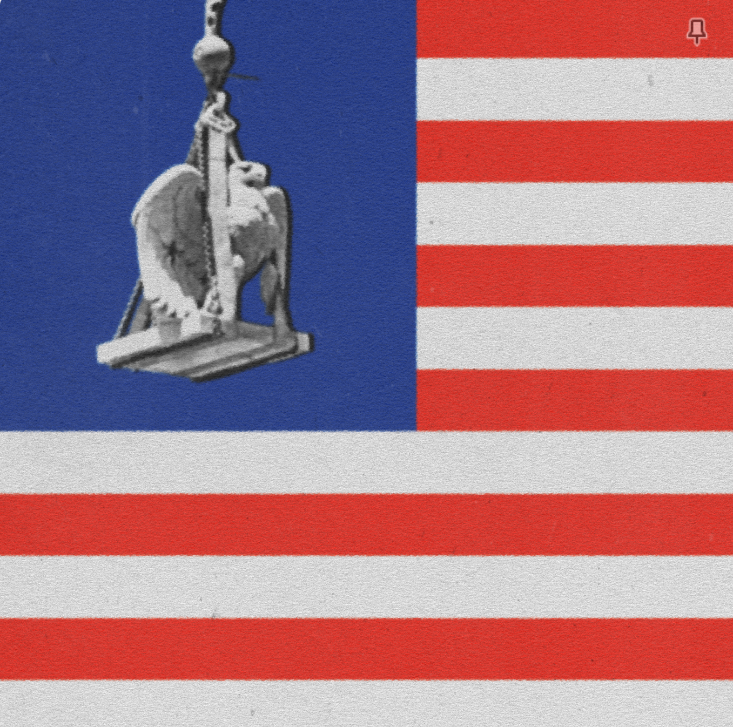

There’s a good chance you’ve been to Penn Station. And if you’ve been to Penn Station, there’s a better chance you didn’t quite enjoy being in Penn Station. This is for good reason, too— it’s a chaotic set of suffocating tunnels filled with exposed wire, low ceilings, and a generally awful atmosphere. It gets far, far worse, however: we used to have a solution. If the demolition of a building is regarded as a death, per se, then the tearing down of the original Penn Station in 1963 is like a murder. Cold-hearted, brutal, done in with the swift dance of the wrecking ball like too many Manhattan masterpieces, the demolition is regarded by many as the greatest insult to commuters there has yet to be. Now, however, a growing crowd calls for a new plan— bringing it back from the dead.

First, the context. Then, the consequences.

The MTA and Port Authority, of course, are not indifferent to this hatred. Attempts have been made, but these have generally been ineffective at solving the critical problem of Penn itself. In June of ‘23, Governor Kathy Hochul announced hesitant plans to reconstruct parts of the station— this has since exploded into a cacophony of voices from all sides with stakes in the station. NJ Transit and Amtrak say they need more space. Hochul’s proposal retains much of the current design. ASTM, a private developer, threw its hat into the ring with a full renovation and a partial demolition of Madison Square Garden. Penn sits unchanged regardless. In this mess, a front started to form.

It started with a website. Rebuildpennstation.org (now refreshed as grandpenn.org), and their plan to “return the station to its former grandeur”, began making appearances in Architectural Digest, The Wall Street Journal, then The New York Post. The idea of resurrecting the Penn Station of old has become a genuine movement with serious legitimacy. Great news, no?

As much as I hate to be a buzzkill— don’t worry, I hate the new Penn too— the original station has many problems when it comes to functioning as a modern transportation hub. It’s just as impractical as the new station in many ways— it was designed for far less commuter traffic than even the current station was, lacks the space for many modern amenities, and boasts open-air platforms largely impractical today. Now, the Grand Penn proposal remedies much of this by redesigning numerous parts of the station, but this doesn’t take away from the most concerning question that comes to mind— why are we rebuilding the original? Why not design a new station from scratch?

This is the same question I was asking a few days ago when the Trump administration re-approved the Executive Order on Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture, a mandate to have all new government buildings built in the US be restricted to traditionalist styles. Think white marble, ornate columns, Greek pediments. This creates a dangerous standard— an omnipotent authority, in a sense, that dictates what’s aesthetically acceptable and what’s not. Even though this mandate deprives new styles from flourishing in governmental architecture, there’s little doubt major institutions double down— in fact, it seems like some are hedging on it.

When I asked Justin Shubow, president of the National Civic Arts Society and head of the Grand Penn proposal, if there was concern to be had over such a return to the architecture of old, he replied, for lack of a better word, bluntly. “ There is no reason to think there would be deprivation.” It’s— well, it’s concerning, to say the least. No reason. According to Mr. Shubow, classical architecture can “situate ourselves within Western Civilization”— a sentiment concerningly wrought with the idealist purism of old. A philosophy that, keep in mind, spurred imperialism. Across the still-developing world, the same architecture praised here is a sorrowful reminder of another time. Scars of a colonial past. What kind of a feeling was this style meant to instill?

What, exactly, are we situating ourselves in?

The US isn’t the only government forcing a traditionalist mindset— Hungary, under Viktor Orban, has set out to resurrect a castle in the center of Budapest. On paper, their mission, to restore the castle to “how it used to be”, seems of noble intention, but why that version of Duba Castle? It wasn’t the first, nor the longest-lasting version of the castle. At the time of its destruction, it was only about as old as buildings built in the 1980s are today— in fact, it was newer than the current Penn Station is now. What’s far more likely— almost a certainty, given Orban’s other actions to twist his image while in power— is that this castle was simply the grandest. This castle was the wealthiest, most gilded, most out-there piece of architecture ever seen in Hungary at the time, and of course, it was home to the monarchy. That is just what Orban wants to come to mind when his new crown jewel is seen: his regime wishes to be seen as the aristocracy, the dominant power dictating what’s acceptable and what’s not. The omnipotent. Authority.

These don’t seem related. That’s true. A new (old?) Penn is certainly a long shot from a castle in Hungary or even the state of architecture in Washington. But there is a connection— a through-line, intentional or not— and to show it to you, I’m going to have to go a bit closer to home.

Glen Ridge itself is an undeniably beautiful example of traditional residential architecture. We have, concentrated within this square mile and a half, one of the greatest collections of Victorian, Foursquare, Dutch Colonial, and Spanish Revival architecture in the New York area. We pass out awards to well-executed architectural preservations, our avenues sit lined with sycamores— our own train station, a far cry from Penn, sits quietly as a shingled Victorian propped above the tracks. Very little in town was built after the 1920s— that which was, mostly done through the ‘60s and ‘70s, has since been demolished and replaced with more traditional designs. Such uniform aesthetic quality is thanks to the Glen Ridge Historical Preservation Commission, which mandates, along with the zoning codes of the town, what can be built and what can’t be. Their job typically involves making sure new construction and renovations fit nicely within the existing architectural fabric of the town. This is hard work, and good work, at that— but it’s hard to ignore the sadder undertones of it all. Across the country, architectural heritage is often an excuse used to justify shooting down proposals for denser housing and lower-income development. In keeping architecture to the status quo, we keep economic and social lines just the same. Now, there’s no nefarious plot behind Glen Ridge’s architectural preservation— such consequences are entirely unintended— but we need to recognize what we do when we attach ourselves to maintaining a strict traditionalist architectural mindset.

So what does it mean when our government, no longer unintentionally, supports this? What does it mean when we lend our name to this architecture? Mr. Shubow told me a classical station represents “the architecture of American democracy.” But should our democracy, then, like our architecture, be stuck in marble and stone? Rising conservatives latch onto traditionalist architecture because it represents an unflinching authority, one that must be respected above all else. The version of Duba Castle Orban feverishly wishes to resurrect was only built because the previous one was deemed insufficient for the Hungarian monarchy. Trump sees marble pediments as barricades against the problems of our country. The map in the waiting room of the rebuilt Penn Station proposal, as it did in the original, includes only Europe and North America. When people in power force traditionalist architecture, it means an unwillingness to accept change. And change, you and I both know, is what we need right now. But what can we do? A lot, actually— Get involved in local urban planning! Support fresh designs! Make noise! So yes, Penn Station sucks. But like it or not, we need new life, not a resurrection.