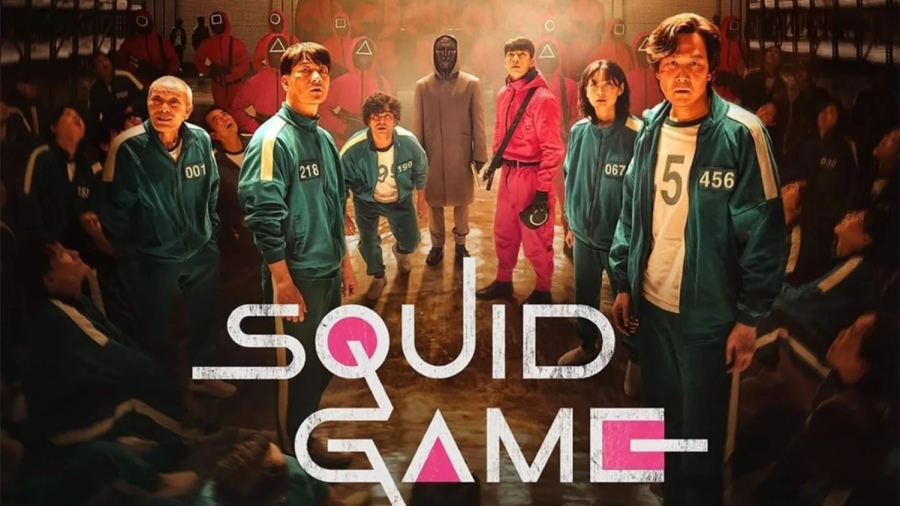

Squid Game Review

December 5, 2021

SPOILERS AHEAD

Hwang Dong-hyuk’s “Squid Game” describes a contest with 456 participants in which the winner receives unlimited money if they can survive a harsh circuit of deadly situations. These challenges are based on kids’ playground games, which adds a layer of irony to how cruel they become: for example, in the first stage, a variant of “Red Light, Green Light” in which those who move after “Red Light” are killed, more than half of the participants ended up dead by the end of the round.

The brutality is both unsettlingly personal and impersonal: while the contestants’ lives are brought to an end in a brutally honest manner, the gunmen are masked game staff (or, in the case of Red Light, Green Light, a robotic doll). From what we know, random game staff administer death, and we know far less about them than we do about the game’s players. What we progressively discover, thanks to the technique of a broken-in investigator, is that they are completely bought-in, following their own set of rules and believing firmly in a game they’ve worked hard to convey with a certain ornate innocence.

This reality — that both participants and staff are tied by necessity and an odd attachment to the game’s rhythms — has simple, basic lines. It’s structurally sound and appears to be brilliant at first sight. So does the show’s structure at the beginning, when remaining contestants are given the option to quit after the first massacre, only to rejoin against their choice because they are desperate for money — and with a North Korean defector and a Pakistani migrant worker, their circumstances offer a truly fascinating cross-section of modern Korean culture. We’re forced to confront the thought that microscopic chances of survival in the Squid Game could simply be preferable than none in modern society, given that we’ve seen both the awful reality they face in the game and at home.

As the story progresses, it becomes evident that the Squid Game has a variety of purposes, including the harvesting of human parts from the dead and providing entertainment for a social class of affluent individuals — some of whom are represented as white Westerners — who gamble on the outcome. There doesn’t seem to be much to say about the first episode, save that it’s astonishing that the series discovered a way to be even more effectually straightforward and unconcerned with exposing how the human body may fall apart. Concerning the second, there appears to be inadequate irony or even genuine comprehension that the show is urging its audience to do much the same thing as the despised viewers.

To be clear, well before Hwang’s writing dramatically stretches it out, there is a concise distinction between spectatorship of genuine and fictitious violence. However, if the victims had been slain in the pursuit of a more fascinating principle than that injustice is bad, it may be simpler to discern the difference. The competition was, in essence, meant for amusement and to discover if people can be ethical, according to a season-ending chat between the game’s victor and its inventor (despite seeing numerous people demonstrate collaboration, selflessness, and cooperation, he feels they aren’t).

Rated: TV-MA